Fetische / Fetishes / Fétiches

In André Bretons Novelle Nadja begegnet die Protagonistin in der Wohnung des Autors einem sogenannten "Fetisch" aus den Osterinseln. “Ich liebe dich”, scheint die Statue zu ihr zu sagen, “ich liebe dich, ich liebe dich”. Das von Menschenhänden gemachte Ding spricht zu ihr, wie eine Person zur anderen. Die Worte, die wirken wie eine rituelle Beschwörungsformel, sind nicht an das Objekt gerichtet, sondern an das Subjekt, dass vor ihm steht. Und plötzlich ist nicht mehr klar, wer hier wen anschaut, wer hier wen begehrt.

Vom Portugisischen Wort feitico – etwas gemachtes – abstammend, wurde der Begriff "Fetisch" im kolonialen Diskurs für rituelle Objekte ganz unterschiedlicher Kulturen gebräuchlich, denen durch Beopferung oder rituelle Anbetung eine "höhere Macht" eingeschrieben wurde. Die Begegnung in Nadja zeigt auf, wie koloniale Sammlungspraktiken solche Objekte gewaltsam aus ihren "ursprünglichen" Kontexten rissen, und wie sie in neuen Kontexten andere Bedeutungen annahmen: So wurde der "Fetisch" im Zug des "Primitivismus" der europäischen Moderne zu einer Form der Kritik an der eigenen Kultur und auch der Idee von Kultur an sich. Für Marx war der Begriff ein Werkzeug, die überhöhte Bedeutung der Ware im Kapitalismus als Illusion zu entlarven, während Freud damit das Phänomen beschrieb, wobei bestimmte Objekte oder Materialien verdrängte sexuelle Wünsche symbolisieren und befriedigen können. Fetischismus entwickelte sich zu einer vielschichtigen Praxis, die unsere mehrdeutige und oft schwierige Beziehung zu Objekten verkörpert.

Dies trifft besonders auch auf das Verhältnis von Künstlern, Betrachtern und Kunstwerken zu. George Bataille hat angeblich einmal gesagt, kein Sammler könne ein Kunstwerk so sehr lieben wie ein Fetischist einen Schuh – aber als Waren, die unter beinah kultischen Bedingungen an Kunstmessen gehandelt werden, sind Kunstwerke natürlich selber auch Fetische. Als Dinge, in die immer wieder erneut Begehren, Wünsche, und Bedeutungen investiert werden, haben sie vielleicht auch dann etwas Fetisch-artiges, wenn sie sich dem Objektcharakter zu entziehen versuchen oder nie als Ware im Schaufenster des Galeristen landen.

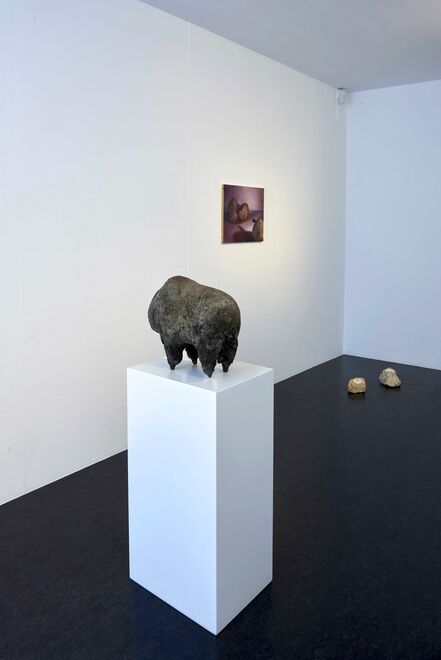

Die Ausstellung vereint Objekte sehr unterschiedlicher Herkunft, wie Fragmente der unterschiedlichen Denkfiguren des Fetisch-Begriffs. Sie inszeniert Begegnungen künstlerischer Arbeiten im Spannungsfeld zwischen Kunstwerk und Fetisch. Arbeiten von Künstlern aus dem Umfeld der Galerie treffen dabei auf Gastbeiträge von anderen Künstlern, sowie auf Objekte aus drei verschiedenen afrikanischen Kulturen. Jetzt Teil der Sammlung des Galeristen Henri Racz, hatte jedes dieser Objekte einmal eine rituelle Funktion, die der ursprünglichen Bedeutung des Wortes "Fetisch" nahe kommt. Im Kontext des 10-jährigen Jubiläums blickt die Galerie mit dieser Ausstellung auch auf ihren Gründungsgedanken zurück, ethnografische Objekte und Gegenwartskunst in einem gegenseitigen Bezug zu zeigen.

Kuratiert von Kate Whitebread

English

In André Breton’s novella Nadja the protagonist, upon visiting the author in his apartment, encounters a so-called "fetish" from the Easter Islands. "I love you", the object appears to say to her, “I love you, I love you”. She perceives the man-made thing speaking to her like one subject to another, in words that sound like a ritual invocation and suggest not just acknowledgement, but desire.

A "fetish” evokes associations for everyone: some think of sex – of shoes, whips or leather – others of ritual objects enclosed in the shadowy display cases of ethnographic museums. Some are reminded of our relationship with the products that surround us, the almost magical power some people invest in a particular design or the latest model of the iPhone. Originally from the Portugese feitico – something that is made – the word was used in colonial discourse to refer to ritual objects of many diverse cultures, within Africa and beyond. These were thought to be invested with "magical" powers through gestures of sacrifice. Although the word “fetish” has largely been discredited as a meaningful term in ethnography, because of its violent colonial history and its lack of specificity, the word continues to have a colourful afterlife.

For one thing, it acquired two powerful additional meanings in the 19th century: For Sigmund Freud, an object could function as a substitute for some other, unconscious sexual desire, thus introducing the idea of the fetish to the realm of sex. Karl Marx suggested that we transform the subjective and social relationships involved in creating economic value into the “fantastic form of a relationship between things”, which he finds analogous to the way religious fetishism invests invisible powers and social relations into objects. Both these ideas are part of our everyday language in a simplified sense today: we have a fetish, in the sense that it triggers some desire (sexual or otherwise); we fetishize things, in the sense that they seem to take on a significance and power that points beyond the thing itself.

The word fetish is therefore, in a sense, itself a fetish: it carries an excess of meaning, embodying many aspects of our relationships with objects – objects that we make, but that seem like things outside of ourselves, with meanings beyond our understanding; as if, like in the example of Nadja above, they were not things, but subjects with an influence of their own. It is not surprising, therefore, that the fetish as an object and fetishism as a practice have both been important in histories of art as well. On the one hand, so-called “fetishes” played an important role in (predominantly) European modernists' critiques of their own culture, or perhaps the notion of "culture" per se. On the other hand, the term became a way of thinking about the relationships between subjects and objects, between artists, viewers and art works. George Bataille once wrote that “no collector could love a work of art as much as a fetishist loves a shoe” – but as commodities, sold in almost cult-like conditions at art fairs, art works are of course themselves fetishes. As objects continuously invested and re-invested with desires and meanings, they are perhaps fetishes even if never sold.

The encounter described in Nadja also shows how ritual objects from other cultures were displayed in proximity with modernist art works – in Breton’s case, the “fetish” stood next to a painting by Max Ernst. Colonial collection practices violently removed these objects from the contexts in which they were first encountered, presenting them either as works of art in the modernist sense (emphasizing their formal aspects over their cultural meaning) or in ethnographic museums that sometimes attempt to evoke the “original” religious context of the pieces by showing them in dark spaces, with theatrical lighting, in contrast to the “white cube” treatment associated with fine art. This can be read as a kind of “re-enchantment”, a response to the “disenchantment and demystification” which the film Les statues meurt aussi by Alain Resnais and Chris Marker claimed that African objects were subjected to by being decontextualized in European collections.

The gallery spaces – one is painted a dark grey, the other white – evoke this history of display. The project space, which has its own logic as a chaotic space, with a visible history, disrupts these two opposites, but it also reinforces the strangeness and arbitrariness of the objects that come together in this show, or perhaps in any show at all. In this exhibition, objects of many different origins populate the gallery like fragments of the ambiguous meanings the concept “fetish” has accumulated, staging encounters between work by contemporary artists that have shown at the gallery in the past, with special contributions by other artists and objects from different African cultures, which once had a ritual function close to that described by the word "fetish", collected by gallerist Henri Racz. In the context of the 10-year anniversary of the gallery, the show is a way of looking back at the gallery’s origins of showing ethnographic objects and contemporary art side by side.

Curated by Kate Whitebred